I was recently interviewed on the release of The Viking Sword. Thanks to Leslie S. Lowe and the Historical Novel Society. It was a fun experience and really made me think!

I was recently interviewed on the release of The Viking Sword. Thanks to Leslie S. Lowe and the Historical Novel Society. It was a fun experience and really made me think!

But was this the reason for his feeling of dread? Hard work, dead ends, great effort expended for no result–these were all in a day’s work in a case of the King’s justice. This was something else. He was conscious of a sense of foreboding, as if he was being dragged along by an inexorable Fate, ensnared in a course of events that was building to some terrible climax yet to come.

—The Viking Sword, Chapter 5

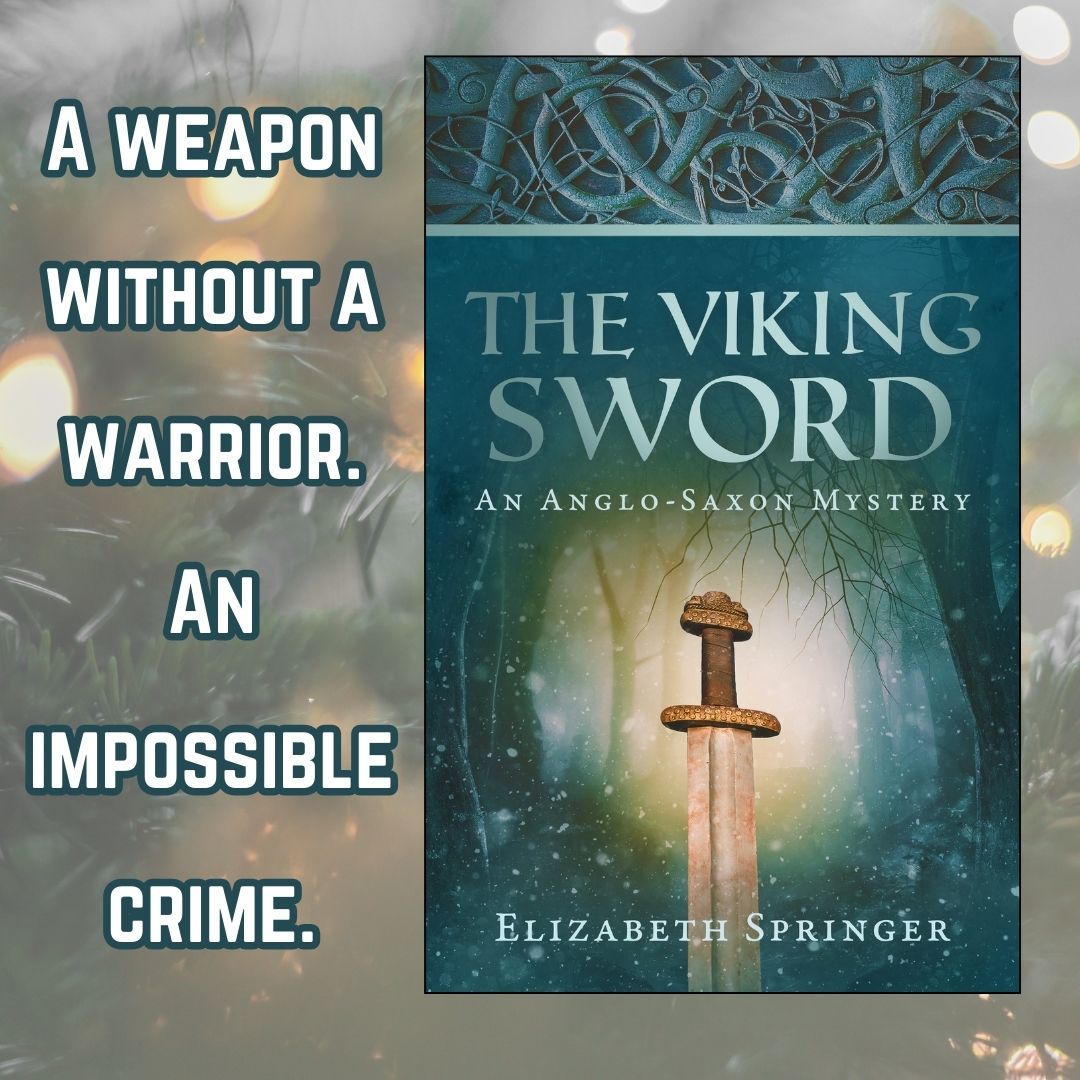

Today I’m happy to announce the publication of the second book in the Edwin of Wimborne Anglo-Saxon mystery series, The Viking Sword. This novel picks up a few months after A Council of Wolves with Edwin and Molly at home for what they incorrectly think will be a peaceful Christmas holiday.

There are several parallel mysteries in this book, two of which take place in locked rooms, and one involves a murder with a Viking sword. There are some missing treasures, an unexplained skeleton, and a kidnapping. Once again, Edwin composes some riddles as well as solving the crime. I had a lot of fun writing the story and I hope you will enjoy reading it.

The Viking Sword is available to order in paperback and ebook from most retail outlets, and you may also be able to request it from your library.

Amazon US: https://a.co/d/cXAbWLl

Amazon UK: https://amzn.eu/d/gDzh81D

Bookshop.org: https://bookshop.org/contributors/elizabeth-springer

Other ebook retailers such as Apple, Kobo, Barnes & Noble, etc.: https://books2read.com/u/49qzD8

Though Christmas has been observed for almost two thousand years, the celebration of the holiday has gone through many permutations over the years. Many of the festive traditions we now associate with Christmas are of relatively recent pedigree, at least in their present forms: Christmas trees, Christmas crackers, Santa Claus, roast turkeys, and so forth. Today, Christmas preparations and celebrations tend to swallow up all of December, and the holiday fizzles out abruptly the day after. Then we have a week of limbo before a final blow-out on New Year’s Eve. I know I’m not alone in finding this all a little exhausting!

How did the Anglo-Saxons celebrate Christmas? Unfortunately, not much information survives. When I say ‘not much information,’ I mean that all that survives from the six hundred years of Anglo-Saxon England are vague, passing mentions in various historical writings of a midwinter holiday being celebrated, as in this well-known passage from the year 878 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

In this year in midwinter after twelfth night the enemy army came stealthily to Chippenham, and occupied the land of the West Saxons and settled there, and drove a great part of the people across the sea, and conquered most of the others; and the people submitted to them, except King Alfred. (trans. Whitelock)

As for other Old English sources, the sermons of the tenth-century preacher Aelfric of Eynsham narrate the story of the Nativity in an endearingly Anglo-Saxon way: “Hi comon ða hrædlice, and gemetton Marian, and Ioseph, and þæt cild geled on anre binne, swa him se engel cydde,” which translates, “They came then quickly, and found Mary, and Joseph, and the child laid in a bin,* as the angel had announced to them.” There is also some strikingly beautiful religious poetry that shows that the Anglo-Saxons thought and felt deeply about the theological significance of this great day—on that more below.

*The Normans had not yet invaded and changed all the bins into mangers.

The basics

Just in case we are getting ahead of ourselves, let’s go back to the very beginning. What is Christmas? It is the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ, the Son of God by the virgin Mary, in Bethlehem, as described in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the Bible (the Gospels of Mark and John do not include narratives of Jesus’ birth). Although the exact date of Christ’s birth was never recorded, early in church history the feast began to be celebrated around the time of the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, which in the northern hemisphere occurs on December 21.

In 597, the Council of Tours instituted the twelve days between December 25 and January 6 as an official feast, to be preceded by a period of fasting during Advent.

Advent

This period of Advent fasting during the darkening days of December is a factor that has been largely lost sight of in modern times. Advent was traditionally the time when Christians would remember the long centuries of waiting for the promised Messiah to come (‘advent’ means ‘coming’) and release his people from slavery to sin. In the modern world we have our ‘fast’, as it were, in January, when we try to get our lifestyle back on track after a month of indulgence.

Some of the very oldest songs now considered Christmas carols are really Advent hymns. “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” (tune: DIVINUM MYSTERIUM) “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” (tune: PICARDY) and “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” (tune: VENI EMMANUEL) are three well-known examples. The words to these hymns date to the late Roman and early medieval periods, and were translated into English in the Victorian era. The haunting minor-key tunes that are now used to accompany the hymns date to the Late Medieval and Renaissance periods—so these Advent hymns represent layer upon layer of church history.

“O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” is based on the O Antiphons, advent poems in Latin probably written in Italy and dating to the sixth century. Each of these poems is a ‘cento’—a poem made up of quotations from other works, in this case Bible verses. The O Antiphons were known in the Anglo-Saxon period and inspired an ‘expanded version’ which is found in the Exeter Book. These poems explore the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy in the birth of Christ. See Eleanor Parker’s blog for an excellent translation and discussion of these poems. https://aclerkofoxford.blogspot.com/2013/12/the-anglo-saxon-o-antiphons-o-clavis.html

Yule, Midwinter, and Christmas

Yule, or Geola (with g pronounced as y) is the old pre-Christian name for the midwinter holiday, named after the months of December-January in which it occurred. Bede wrote in his De temporum ratione (The Reckoning of Time) that the pagan Anglo-Saxons celebrated a festival at the end of December. What they celebrated, or how they celebrated, Bede did not know; he merely notes that the night of December 25 was referred to as Modranecht, ‘Mother’s Night,’ probably because of some kind of ceremony they did back then.

Yule has remained a synonym for Christmastime in English ever since. In Scandinavia, it is the only name for Christmas! The name for the Christian holiday attested during Edwin and Molly’s time is Middewinter. The name Cristesmaesse appears in Old English documents around the year 1000. In The Viking Sword, I alternated these names as a compromise between historical authenticity and the desire to evoke the strong seasonal associations of modern readers with the word Christmas.

Fact and Fiction

So you see my predicament. As I worked on The Viking Sword, I found myself in the same situation as when I had to portray Edwin and Molly’s wedding in A Council of Wolves—there is a distinct lack of source material about how these special days were celebrated. What’s an author to do? Scholarly and popular history writing is full of ‘maybes’ and ‘might haves’ concerning how Christmas was celebrated so long ago, and that is entirely proper. But when you are writing a novel, you have to weigh the ‘maybes’ and ‘might haves,’ and decide on something for your characters to do in the world you have created for them. With this in mind, I included a few seasonal traditions that seemed most likely to have been followed in the ninth century.

Yule logs

The Yule log seems like a very ancient tradition, and it may very well be, but I was surprised to find out that there’s no firm evidence one way or the other. The first written reference in English to a special log that is burned at Christmas dates to 1648, when the poet Robert Herrick mentions a ‘Christmas log,’ and the term ‘Yule log’ appears in other sources around the same time. However, the tradition of having a massive log that you light at midnight on Christmas Eve is a tradition found throughout Europe. As a scholar, I could not make a convicing case from the existing source material that the Anglo-Saxons certainly had a Yule log tradition. As a historical novelist, however, I saw no reason why they should not have one, since the Yule log is such a long-standing and widespread custom. And since holly and ivy are the principal native evergreens in England, I allowed the Anglo-Saxon halls in the novel to be decked with them, though there is no explicit evidence that I know of for that, either.

The Advent fast was broken on Christmas Day when the twelve days of Christmas began. Some of the days within the twelve-day feast had their own dedication or significance: the 26th was St. Stephen’s Day, the 27th was the feast of St. John, the 28th was Childermas (Feast of the Holy Innocents), the 31st was St. Sylvester’s Day, and the 1st of January was the feast of Christ’s circumcision, as it falls eight days after the 25th.

Anytime between Christmas Day and Epiphany (January 6) may have been the traditional time to give gifts. In the eighth century, Ecgbert, Bishop of York wrote that the English customarily gave alms to monasteries and to the poor before and during the twelve days of Christmas. A king such as Alfred didn’t just give to monasteries at Christmas—he gave two monasteries to his friend Bishop Asser, along with a silk cloak and a quantity of incense weighing the same as a man (Asser’s Life of King Alfred, par. 81). Christmas is also a common date on charters, so apparently the king and court got some business done as well while they were all together in one place. The celebrations continued until Epiphany, the traditional date when the visit of the Magi to the infant Christ was celebrated (see Matthew chapter 2).

Which brings me to the Kings’ Cake eaten at the end of The Viking Sword. This cake is to celebrate the arrival of the Three Kings in Bethlehem. (The Bible speaks of an unspecified number of wise men, or as Aelfric calls them, tungel-witegan, ‘star-wise-men,’ bearing three gifts of prophetic significance for the baby Jesus.)

The King Cake tradition is said to derive from Saturnalia, the ancient Roman winter holiday when masters and servants traded places for a week of madcap highjinks and shenanigans. Typically, some small inedible item is hidden in the King Cake. Whoever gets the item—a coin, a bean, a plastic baby—either receives some benefit or privilege, like good luck or getting to be the Lord of Misrule (hence the Saturnalia connection), or has some duty, like buying the King Cake for the office next year. King Cake, also called Twelfth-night Cake, is documented as an English tradition from the Middle Ages into the 18th century, but died away during the Industrial Revolution. It is still popular in continental European countries and in my father’s home state of Louisiana. The “holiday cake with hidden prize” tradition survives in some British family traditions in which a coin is hidden in the Christmas cake or pudding. This tradition has given rise to at least one great British mystery story, “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding” by Agatha Christie (dramatized as The Theft of the Royal Ruby in 1990).

Because of the Louisiana connection, I have always associated King Cake with Mardi Gras (known in England as Shrove Tuesday or Pancake Day). This is the day before Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the Lenten fast, forty days before Easter—a different season and holiday altogether! Pleasure-loving Louisianians consider King Cake season to stretch from Epiphany until Mardi Gras. That gives everyone in the state plenty of time to enjoy this indulgent seasonal treat.

Back to Christmas in the days of King Alfred. Though I write fiction, I want to portray the history and culture of ninth-century Wessex as accurately as possible. I have had to sift through the bare bones of information available from the period, piece together what is likely based on surviving customs, and breathe life into these relics using my own experience about what people consider to be appropriate to a special life celebration or holiday.

Almost everywhere in the world on such occasions there will be special food and drink, special religious observances and music, a change of home decorations and clothing, exchange of gifts, and shared family rituals or traditions like dancing and games. If all the expected elements are included, people have a sense of a holiday properly celebrated, everyday routine suspended, a moment in the year marked. Strong feelings may be stirred if a cherished tradition is neglected, or if a person has to miss an event while others celebrate. In my portrayal of Edwin and Molly’s first Christmas together, I’ve tried to imagine how Anglo-Saxon people would feel about little details of the holiday and what they would find most meaningful. I hope this aspect rings true, and helps you, the reader, enter deeper into the story. The choice to set The Viking Sword at Christmas has given me a whole new appreciation of Christmas and how it was celebrated in the past, and I’m glad to have the opportunity to share this appreciation with you.

This series features some of my favorite historical fiction and mystery authors.

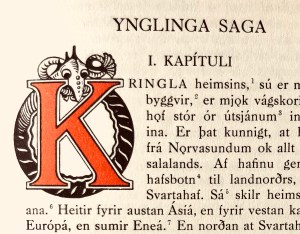

The cover of the Norwegian translation of Heimskringla by Gustav Storm, published 1900. The entire book is a work of art.

Snorri Sturluson (1178/9-1241) belongs in my series of favorite authors as a pioneer of what might be called biographical historical fiction, and as a poet and teacher of poets. As such, he serves in this series as my figurehead for a whole ‘school’ of now-anonymous saga writers of medieval Iceland, who took the characters, events, and landscapes of Iceland’s recent past and created remarkable prose narratives that deserve to be considered early historical fiction.

What is a saga?

The word ‘saga’ is bandied about quite a bit. What do I mean by an Icelandic saga? The Oxford English Dictionary defines a saga as “any of the narrative compositions in prose that were written in Iceland or Norway during the middle ages.” The second definition suggests transference of meaning: “a narrative having the (real or supposed) characteristics of the Icelandic sagas; a story of heroic achievement or marvellous adventure.”

The king’s men bring their loot aboard. From Gustav Storm’s Norwegian translation of Heimskringla (1900).

An Icelandic saga is a long-form prose narrative, about the length of a modern novel or novella, that tells a story about a person or group of people. The word ‘saga’ is taken from Old Norse and means, approximately, ‘that which is said,’ suggesting that these narratives were once oral tales; but those days were already passing when the sagas were written down as intentional works of literary art. Although the authors make an attempt to portray historical characters and events in a way that would have been recognized as true and reliable by their audience, the fabric of a saga narrative is also an imaginative product, and that’s why I have called it ‘historical fiction’ here. The sagas are written in an objective style and tend to focus on outward actions with minimal authorial commentary. The interpretation of characters’ inner feelings and motives is usually left to the reader. There are different sub-genres of sagas: the ‘sagas of Icelanders’ or Icelandic family sagas tell the story of several generations of a family, usually centering on one person or key event. Kings’ sagas (of which Snorri wrote many) tell the story of a king; most of these are about kings of Norway. There are bishops’ sagas, saints’ sagas, and mythological and legendary sagas based on Germanic legend and contemporary Arthurian romance.

Tempestuous times in Viken.

About Snorri

As he emerges from historical sources, Snorri Sturluson was a multi-faceted man; but he had two main sides, the political and the literary. He lived during a tempestuous time in Iceland’s history, when internal dissension led to a power vacuum soon filled by Norway (this was Norway’s historical moment of being a colonial power). He was a member of the powerful Sturlung family, the richest man in the country, and consequently was propelled to the top of the Icelandic political ladder, becoming law-speaker (leader of the national assembly) while still in his thirties. He married the richest woman in Iceland and they had several children.

On the literary side, he was brought up among the Oddaverjar, a family of chieftains whose farm Oddi was a center of learning. Surely it was here that he developed the literary talents that later led to composition of his series of sixteen sagas of the Norwegian kings (known collectively as Heimskringla) and his prose Edda. He may have written other sagas as well, but authorship of other surviving works is uncertain.

Heimskringla

The beginning of Heimskringla, “Kringla heimsins,” from the first volume of the Islenzk Fornrit edition. This is the original Old Norse language in which sagas were written.

The title Heimskringla, which means ‘the circle of the world,’ is taken from the first word in the book. This is not one saga but a collection of sagas of varying lengths, each taking as its main character one of the Norwegian kings. It begins in legendary times with the Saga of the Ynglings and ends with the Saga of Magnús Erlingsson in the late twelfth century. The centerpiece and longest saga is the Saga of St Óláf, which takes up the middle third of the collection. As you might expect, Heimskringla is full of battles and adventures, but you also find lots of details about everyday life, courtship and etiquette, travel, folklore, and humor.

Saint Óláf’s Saga (Heimskringla), Chapter 85

There was a certain man called Thórarin Nefjólfsson. He was an Icelander whose kin lived in the northern quarter of the land. He was not of high birth, but he had a keen mind and was ready of speech. He was not afraid to speak frankly to men of princely birth. He had been on long journeys as a merchant and had been abroad for a long time. Thórarin was exceedingly ugly, and particularly his limbs. He had big and misshapen hands, but his feet were uglier even by far. At the time when the occurrence told above took place, Thórarin happened to be in Tunsberg. King Óláf knew him and had spoken to him. He was getting the merchant ships he owned ready for sailing to Iceland in the summer. King Óláf had invited Thórarin to stay with him for a few days and used to converse with him. Thorarin slept in the king’s lodgings.

One morning early the king awoke while other men were still asleep in the lodgings. The sun had just risen, and the room was in broad daylight. The king observed that Thórarin had stuck one of his feet outside of the bed-clothes. He looked at the foot for a while. Just then the other men in the lodging awoke.

The king said to Thórarin, “I have been awake for a while, and I have seen a sight which seems to me worth seeing, and that is, a man’s foot so ugly that I don’t think there is an uglier one here in this town.” And he called on others to look at it and see whether they thought so too. And all who looked at it agreed that this was the case.

Thórarin understood what it was they talked about and said, “There are few things so unusual that their likes cannot be found, and that is most likely true here too.”

The king said, “I rather warrant you that there isn’t an equally ugly foot to be found, and I would even be willing to bet on that.”

Then Thórarin said, “I am ready to wager with you that I can find a foot here in town which is even uglier.”

The king said, “Then let the one of us who is right ask a favor from the other.”

“So let it be,” replied Thórarin. He stuck out his other foot from under the bed-clothes, and that one was in no wise prettier than the other. It lacked the big toe. Then Thórarin said, “Look here, sire, at my other foot. That is so much uglier for lacking a toe. I have won.”

The king replied, “The first foot is uglier because there are five hideous toes on it, whilst this one has only four. So it is I who has the right to ask a favor of you.”

Thórarin said, “Precious are the king’s words. What would you have me do?”The English translation of Heimskringla by Lee M. Hollander includes many of the Norwegian woodcut illustrations.

Snorri’s Edda

Interspersed in many of the sagas are snatches of poetry of a very special kind that are used by the saga authors as references or historical sources. This poetry was composed by skalds, professional poets who often served in the court of a nobleman or king. The structure of a skaldic poem is very intricate—I won’t try to explain the finer points here. The verses were made up of convoluted metaphors called kennings. When you compose with kennings, nothing is called by its own name: gold might be called ‘the crucible’s load,’ since it is refined in a crucible, and a man’s arm might be ‘the falcon’s perch,’ since in falconry you carry the bird on your arm. Thus, if a skald wanted to praise a ruler for generously handing out golden arm-rings to his retainers, he might say the ruler was a giver of the crucible’s load to adorn the falcon’s perch. Many of these kennings, however, have built-in references to Norse mythology. In the Christianized time and place in which Snorri lived, myth-based kennings were losing their meaning and devolving into nonsense for young poets.

Gylfi with High, Just-As-High, and Third, from the Uppsala manuscript of Snorri’s Edda, Uppsala University Library, DG 11, f. 26v.

Snorri wrote his Edda to explain Norse mythology and how to use it in kennings in skaldic poetry. It falls into four main parts: the Prologue, which explains how Norse mythology joins up with Genesis and Greek learning; Gylfaginning (The tricking of Gylfi), framed as a sort of fairy tale in which a mythical King Gylfi of Sweden goes on a journey and comes to a hall presided over by three mysterious kings called High, Just-As-High, and Third. He questions them and their answers are stories from Norse mythology. The third section, Skáldskaparmál, explains how kennings work and how to use them. It also contains many important myths, provided as explanations for why certain kennings exist. These two sections are our chief sources for knowledge about Norse mythology. All the Norse myths you have ever read in your life come from these sections of Snorri’s Edda and from the Poetic Edda, an anonymous collection of mythological poems. The fourth section of Snorri’s Edda, Hattatál, is a sampler of different verse forms and how they are composed.

Recommended reading

I recommend Anthony Faulkes’ translation of Snorri’s Edda, published by Everyman.

Heimskringla is available in a good translation by Lee M. Hollander (University of Texas Press) with many of the original woodcuts by various artists from the classic Norwegian translation by Gustav Storm published in 1900.

A selection of anonymous Icelandic sagas. There are many more, but these are some of the most famous:

Egils Saga, trans. Christine Fell and John Lucas, Everyman. (The Penguin translation is also good, but Christine Fell was one of my professors at Nottingham, so I have a particular affection for hers.)

Njal’s Saga, trans. Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America, trans. Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

Hrafnkel’s Saga and Other Stories, trans. Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

The Saga of the Volsungs, trans. Jesse Byock, Hisarlik Press.

Read a saga, or risk the King of Sweden’s anger!

My first Anglo-Saxon mystery will be published very soon. Stay tuned!

A blog about the Edwin of Wimborne medieval mystery series, the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, and detective fiction.

Spoiler-Free Reviews of Fair Play Detective Fiction

A blog about the Edwin of Wimborne medieval mystery series, the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, and detective fiction.

A blog about the Edwin of Wimborne medieval mystery series, the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, and detective fiction.