In this post, I interview author and historian Annie Whitehead about her new study of historical Anglo-Saxon murders. When I saw this book was coming out, I had to buy and read it!

Elizabeth Springer: Give a brief description of your latest book, Murder in Anglo-Saxon England.

Annie Whitehead: When I’m writing and researching I’m always aware of the more famous, or should I say notorious, murder stories from the period, and I decided it would be fun to investigate all the tales I could find, to see whether they are based on fact, and why later chroniclers might have embellished them. So this is a collection of those stories, which I decoded as much as possible to see if they are true. I also looked at the justice system, the notion of ‘blood feud’, and I thought about a number of recorded deaths which were so timely that I wondered if those who stood most to benefit from them were actually culpable.

ES: Tell a little about your background. How did you become interested in Anglo-Saxon England? About this particular book: what was your inspiration? Tell me about your methods and sources.

AW: I’m a history graduate and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. I write both fiction and nonfiction books and short stories. I’ve always been interested in history, probably stemming from the time I lived in York when I was eight—there is so much rich history there. I think this latest book was the logical next step for me in terms of nonfiction, as I’d already written a history of the ancient kingdom of Mercia, and a book about the women of the era. Both of these contain some of the murder stories and I decided that they, along with many others, warranted a revisit and further analysis. I always start the research with the earliest contemporary sources and make my way forwards from there. The later the chronicle, the more detail, but also the more exaggeration, so I have to be careful when I’m searching for the facts.

ES: The book could have been called “Political Assassinations in Anglo-Saxon England.” Why do the sources focus on murders of prominent people?

AW: The sources only mention the higher ranks of society, which is frustrating. I have included some chapters about laws (which technically applied to everyone, although the nobility do seem to have murdered with impunity at times) and about execution cemeteries. I found a few legal cases which pertained to lower-ranking nobility, but sadly the common people were not given the same attention by the chroniclers.

ES: Tell about wergild. What was it? What was its purpose?

AW: Wergild was essentially ‘man-price’, a figure based on one’s place in society, and the value placed on one’s life, payable to kin in the event of a killing. If the murderer couldn’t pay, then the lord, or the perpetrator’s kin, were liable, so in a way it was designed to stop such things happening.

ES: Why was Anglo-Saxon law more focused on theft than murder?

AW: I think it has always been thus, and seems to have been true even up to Victorian times, when children were being hanged for theft. It is possible to argue that murder wasn’t a priority because it wasn’t prevalent, although we can’t know as in the main we do only have the high-profile cases, but theft, of land, and property, and particularly house-breaking was a concern, with harsh punishment.

ES: What sources do we have for the types of punishment? What were they?

AW: In terms of the death penalty, the method was usually hanging, although there is evidence of beheading, too. Our sources are archaeological, but also we have written laws from the period which set out in great detail the punishment for various crimes. By and large the punishment system was based on the wergild, and it was a compensation system, with fines laid out for even the most minor injuries to major wounding, again, in an effort to stop fights escalating; everyone knew where they stood and what they would stand to lose if they broke the law. I say ‘everyone’ but again I must say that the higher ranks often got away with it.

ES: Tell us about different methods of murder in the book.

AW: There is such a variety: an assassination attempt with a poisoned blade, child murders, ambushes (quite often a betrayal by a family member or friend, who would lure the victim into the woods under the false promise of a hunting trip), poison (women in particular were accused of poison), witchcraft, and even death by scissors! We also have murders sanctioned by kings, from mass murder to individual assassinations. There’s an examination of the myths and legends surrounding the Blood Eagle, and of the notion of blood feud, extending across generations.

ES: What is forcible tonsure, and why did it exclude the recipient/victim from kingship?

AW: Forcible tonsure (the shaving of the head in the manner of monks) was common, not only in England but also on the Continent, and we hear of it often, particularly in the earlier part of the period. Essentially it meant forcing someone, a rival claimant to the throne, to become a tonsured monk. As a tonsured monk or clergyman, he forfeited his property, mobility, and right to marry, and was thus ineligible to rule. It was a neat way of eliminating his claim without actually killing him.

ES: Do you have a favorite murder story in the book? Are there any you think would make a good plot for a detective novel? Asking for a friend…

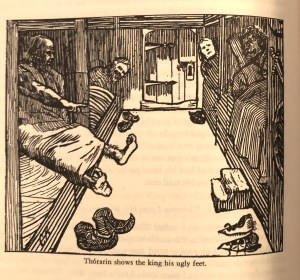

AW: One of my favourites concerns an abbess, daughter of a king, who was reputedly jealous that her young brother (a child) succeeded their father. She arranged to have him murdered, but was found out when his soul flew up in the form of a dove which dropped a message on an altar in Rome saying what had happened and where the body could be found. When the funeral procession came back to the abbey, she chanted a spell, but her eyeballs fell out. I love this story because of the gory and frankly fantastic detail, but also because we actually have little to no evidence that her little brother even existed. It’s a classic case of embroidering by the later chroniclers.

I’m not sure about murder mystery as a plot for detective novels because when murders are recorded, the chroniclers name the culprit. But it would be interesting for a medieval detective to go off in search of hard evidence that would exonerate them, because in many of the cases I’ve looked at for the book, the evidence for their guilt is not compelling.

[Elizabeth Springer comments: Great idea! The little wheels are turning in my head already…]

ES: What surprised you in your research?

AW: I think one surprise, or at least a realisation, was the extent to which murder went unpunished. We have many cases where we have details of punishment, and high-profile cases of wergild being paid, but far more where no one was held accountable. It was also interesting that one was more likely to die for theft than murder, something I hadn’t really noted before I started writing the book.

ES: You’ve written quite a few books, both fiction and non-fiction. What topics have you written about? Where can readers purchase your books?

AW: I’ve written four novels featuring prominent Mercian characters, including Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, and Penda, the last pagan king. I’ve also written three nonfiction books, one about the history of Mercia, one about women of the era, as well as Murder in Anglo-Saxon England. I’ve also contributed to two nonfiction anthologies and three fiction collections, with another due out later this year.

Details of all my work and where to buy can be found on my website: https://anniewhiteheadauthor.co.uk/

or on my Amazon Author Page: http://viewauthor.at/Annie-Whitehead

ES: What’s next in your writing career?

AW: I’ve gone back to work on a novel that I shelved while writing and researching Murder in Anglo-Saxon England. It’s set in the tenth century, features Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, and has a murder or two. I have an idea for a sequel, too, so I think I’ll be busy for a while.