This series features some of my favorite historical fiction and mystery authors.

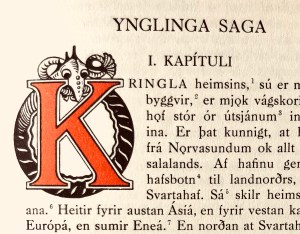

The cover of the Norwegian translation of Heimskringla by Gustav Storm, published 1900. The entire book is a work of art.

Snorri Sturluson (1178/9-1241) belongs in my series of favorite authors as a pioneer of what might be called biographical historical fiction, and as a poet and teacher of poets. As such, he serves in this series as my figurehead for a whole ‘school’ of now-anonymous saga writers of medieval Iceland, who took the characters, events, and landscapes of Iceland’s recent past and created remarkable prose narratives that deserve to be considered early historical fiction.

What is a saga?

The word ‘saga’ is bandied about quite a bit. What do I mean by an Icelandic saga? The Oxford English Dictionary defines a saga as “any of the narrative compositions in prose that were written in Iceland or Norway during the middle ages.” The second definition suggests transference of meaning: “a narrative having the (real or supposed) characteristics of the Icelandic sagas; a story of heroic achievement or marvellous adventure.”

The king’s men bring their loot aboard. From Gustav Storm’s Norwegian translation of Heimskringla (1900).

An Icelandic saga is a long-form prose narrative, about the length of a modern novel or novella, that tells a story about a person or group of people. The word ‘saga’ is taken from Old Norse and means, approximately, ‘that which is said,’ suggesting that these narratives were once oral tales; but those days were already passing when the sagas were written down as intentional works of literary art. Although the authors make an attempt to portray historical characters and events in a way that would have been recognized as true and reliable by their audience, the fabric of a saga narrative is also an imaginative product, and that’s why I have called it ‘historical fiction’ here. The sagas are written in an objective style and tend to focus on outward actions with minimal authorial commentary. The interpretation of characters’ inner feelings and motives is usually left to the reader. There are different sub-genres of sagas: the ‘sagas of Icelanders’ or Icelandic family sagas tell the story of several generations of a family, usually centering on one person or key event. Kings’ sagas (of which Snorri wrote many) tell the story of a king; most of these are about kings of Norway. There are bishops’ sagas, saints’ sagas, and mythological and legendary sagas based on Germanic legend and contemporary Arthurian romance.

Tempestuous times in Viken.

About Snorri

As he emerges from historical sources, Snorri Sturluson was a multi-faceted man; but he had two main sides, the political and the literary. He lived during a tempestuous time in Iceland’s history, when internal dissension led to a power vacuum soon filled by Norway (this was Norway’s historical moment of being a colonial power). He was a member of the powerful Sturlung family, the richest man in the country, and consequently was propelled to the top of the Icelandic political ladder, becoming law-speaker (leader of the national assembly) while still in his thirties. He married the richest woman in Iceland and they had several children.

On the literary side, he was brought up among the Oddaverjar, a family of chieftains whose farm Oddi was a center of learning. Surely it was here that he developed the literary talents that later led to composition of his series of sixteen sagas of the Norwegian kings (known collectively as Heimskringla) and his prose Edda. He may have written other sagas as well, but authorship of other surviving works is uncertain.

Heimskringla

The beginning of Heimskringla, “Kringla heimsins,” from the first volume of the Islenzk Fornrit edition. This is the original Old Norse language in which sagas were written.

The title Heimskringla, which means ‘the circle of the world,’ is taken from the first word in the book. This is not one saga but a collection of sagas of varying lengths, each taking as its main character one of the Norwegian kings. It begins in legendary times with the Saga of the Ynglings and ends with the Saga of Magnús Erlingsson in the late twelfth century. The centerpiece and longest saga is the Saga of St Óláf, which takes up the middle third of the collection. As you might expect, Heimskringla is full of battles and adventures, but you also find lots of details about everyday life, courtship and etiquette, travel, folklore, and humor.

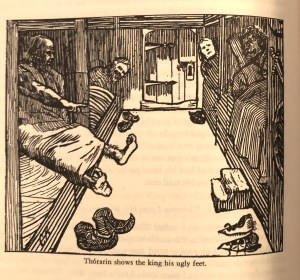

Saint Óláf’s Saga (Heimskringla), Chapter 85

There was a certain man called Thórarin Nefjólfsson. He was an Icelander whose kin lived in the northern quarter of the land. He was not of high birth, but he had a keen mind and was ready of speech. He was not afraid to speak frankly to men of princely birth. He had been on long journeys as a merchant and had been abroad for a long time. Thórarin was exceedingly ugly, and particularly his limbs. He had big and misshapen hands, but his feet were uglier even by far. At the time when the occurrence told above took place, Thórarin happened to be in Tunsberg. King Óláf knew him and had spoken to him. He was getting the merchant ships he owned ready for sailing to Iceland in the summer. King Óláf had invited Thórarin to stay with him for a few days and used to converse with him. Thorarin slept in the king’s lodgings.

One morning early the king awoke while other men were still asleep in the lodgings. The sun had just risen, and the room was in broad daylight. The king observed that Thórarin had stuck one of his feet outside of the bed-clothes. He looked at the foot for a while. Just then the other men in the lodging awoke.

The king said to Thórarin, “I have been awake for a while, and I have seen a sight which seems to me worth seeing, and that is, a man’s foot so ugly that I don’t think there is an uglier one here in this town.” And he called on others to look at it and see whether they thought so too. And all who looked at it agreed that this was the case.

Thórarin understood what it was they talked about and said, “There are few things so unusual that their likes cannot be found, and that is most likely true here too.”

The king said, “I rather warrant you that there isn’t an equally ugly foot to be found, and I would even be willing to bet on that.”

Then Thórarin said, “I am ready to wager with you that I can find a foot here in town which is even uglier.”

The king said, “Then let the one of us who is right ask a favor from the other.”

“So let it be,” replied Thórarin. He stuck out his other foot from under the bed-clothes, and that one was in no wise prettier than the other. It lacked the big toe. Then Thórarin said, “Look here, sire, at my other foot. That is so much uglier for lacking a toe. I have won.”

The king replied, “The first foot is uglier because there are five hideous toes on it, whilst this one has only four. So it is I who has the right to ask a favor of you.”

Thórarin said, “Precious are the king’s words. What would you have me do?”The English translation of Heimskringla by Lee M. Hollander includes many of the Norwegian woodcut illustrations.

Snorri’s Edda

Interspersed in many of the sagas are snatches of poetry of a very special kind that are used by the saga authors as references or historical sources. This poetry was composed by skalds, professional poets who often served in the court of a nobleman or king. The structure of a skaldic poem is very intricate—I won’t try to explain the finer points here. The verses were made up of convoluted metaphors called kennings. When you compose with kennings, nothing is called by its own name: gold might be called ‘the crucible’s load,’ since it is refined in a crucible, and a man’s arm might be ‘the falcon’s perch,’ since in falconry you carry the bird on your arm. Thus, if a skald wanted to praise a ruler for generously handing out golden arm-rings to his retainers, he might say the ruler was a giver of the crucible’s load to adorn the falcon’s perch. Many of these kennings, however, have built-in references to Norse mythology. In the Christianized time and place in which Snorri lived, myth-based kennings were losing their meaning and devolving into nonsense for young poets.

Gylfi with High, Just-As-High, and Third, from the Uppsala manuscript of Snorri’s Edda, Uppsala University Library, DG 11, f. 26v.

Snorri wrote his Edda to explain Norse mythology and how to use it in kennings in skaldic poetry. It falls into four main parts: the Prologue, which explains how Norse mythology joins up with Genesis and Greek learning; Gylfaginning (The tricking of Gylfi), framed as a sort of fairy tale in which a mythical King Gylfi of Sweden goes on a journey and comes to a hall presided over by three mysterious kings called High, Just-As-High, and Third. He questions them and their answers are stories from Norse mythology. The third section, Skáldskaparmál, explains how kennings work and how to use them. It also contains many important myths, provided as explanations for why certain kennings exist. These two sections are our chief sources for knowledge about Norse mythology. All the Norse myths you have ever read in your life come from these sections of Snorri’s Edda and from the Poetic Edda, an anonymous collection of mythological poems. The fourth section of Snorri’s Edda, Hattatál, is a sampler of different verse forms and how they are composed.

Recommended reading

I recommend Anthony Faulkes’ translation of Snorri’s Edda, published by Everyman.

Heimskringla is available in a good translation by Lee M. Hollander (University of Texas Press) with many of the original woodcuts by various artists from the classic Norwegian translation by Gustav Storm published in 1900.

A selection of anonymous Icelandic sagas. There are many more, but these are some of the most famous:

Egils Saga, trans. Christine Fell and John Lucas, Everyman. (The Penguin translation is also good, but Christine Fell was one of my professors at Nottingham, so I have a particular affection for hers.)

Njal’s Saga, trans. Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America, trans. Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

Hrafnkel’s Saga and Other Stories, trans. Hermann Pálsson, Penguin.

The Saga of the Volsungs, trans. Jesse Byock, Hisarlik Press.

Read a saga, or risk the King of Sweden’s anger!